t wasn't teenage concupiscence through which my peers and I established Lara Croft as a 1990s cultural emblem. I checked the historical record: the star of Eidos Interactive's Tomb Raider was exalted in mass media last decade, from print magazines to U2's Popmart world tour. There was a comic book, then a film, and then another film. Well, not concupiscence per se. Video games cast heroines before 1996 — Rosella of Daventry, Princess Peach, Samus Aran. They were female; figurative. Lara Croft, lineamental, was a woman.

If her bustline got everybody's attention, it was Croft's advertised urbanity and daredevil treasure-hunting — propelling clever adventures — by which the character has been sustained. Familiarity extends even to those whose first experience with the series would be this year's Tomb Raider: Underworld, namely, me.

It's certain to leave players

delightfully sweaty-palmed.Having looked at the luminary directly, I would question the endurance of Lara Croft, a phlegmatic and inaccessible character; and the Croft saga, multiple collisions of history, lore and picaresque fiction from radio serials as popularized by one S. Spielberg. But Tomb Raider is a game. Crystal masterminds thrilling puzzles and, as technology provides, ancient and hallowed places heretofore showing only on a movie screen — so I have no questions after all.

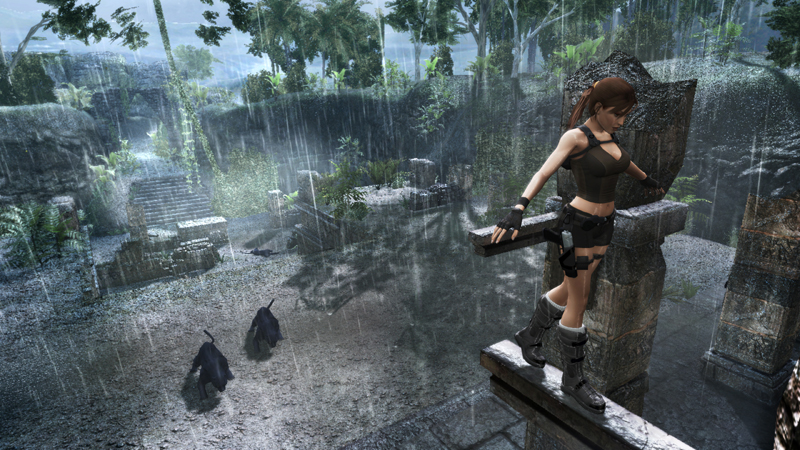

Underworld, in keeping with its genre, sends Lara Croft crisscrossing the world, infiltrating ruins, seeking valuables and confronting the sublime. Narration works from part to whole, cautiously adumbrating whichever big things underpin the fate of Lara, Lara's father and her mother. Go here, do that: Lara is just a half-stride ahead herself. But it's OK: the adventure audience pardons everything except inertia. So Crystal focuses, as surely it has, on the details of platforming gameplay that is both sound and fantastical — making sense at the same time it astonishes. The puzzles designed by Crystal's brain trust share elements — ledges, cantilevers, pulleys, inclines, locks, keys, makeshifts and jury-rigs — while creative arrangement distinguishes each challenge. They are systematic without becoming formulaic, certain to leave players delightfully sweaty-palmed.

Nor without a few flaws, some of them consequences that Crystal, defensibly, has judged acceptable risks. The camera often leaps and swings with Lara — for me, to slightly nauseating effect — and swivels aimlessly in tight spaces while sometimes failing to zoom out when a puzzle's twist demands it. Lara's PDA offers players two hints (one general, one specific), which is handy, but it isn't always relevant and at least once reverted to a prior puzzle — no less, at a point where Lara was required to backtrack, confusing the hell out of me.

Gathering treasures consists of shattering priceless ceramics with a leg sweep. Most of the treasures look like Chihuahua-sized diamonds, and the vases, even tucked away in corners, probably should not have remained untouched. Since the collection exercise measures a player's resourcefulness, it does serve a purpose. But, so antiquated, it detracts from Crystal's craftsmanship elsewhere.

Even with sentimental devotion to a cartoonish face, Lara's bodily articulation is studied and elegant. A world-class athlete provided motion-capture footage; no surprise. But, too, Crystal was thorough. How often over the last ten years has a developer recorded a realistic animation sequence for ascending and descending stairs? Lara stretches, grapples, curls, bends, flips, twists; every movement she makes is that of an acrobatic archaeologist. When she swims, her skin glistens; in rough country, a little mud-flecked and soiled. Not once will a player doubt the performance.

Crystal has preserved

dead ages in grandeur.More impressive than Crystal's characters are the game's environments. They enchant. Many developers, excited by this console generation's hardware, have tried "lush" and instead produced "florid," signally falling short on a depth of field that prevents the eye from settling on a subject. Underworld's ornate temples and underground involutions are redolent of meticulous, color storyboards — imaginative and sharp, but not too sharp. Sound effects lend inconspicuous authority, and just above that level of volume, a mostly ambient soundtrack advises mood. Through size, color, form and feel, Crystal has preserved dead ages in grandeur.

Puzzles packaged in art: a winning property, one that could be widely licensed. Yet under examination it could, and maybe should, operate independently of its lead. As an icon, Lara Croft is strictly two-dimensional. Was she always this insipid? Were her settings and relations always as featureless? Underworld drops the uninitiated into a plot that's apparently meandered for years — a curious new player would have to search for backstory. But what Lara Croft is or isn't intrinsic to is Tomb Raider's success, which Tomb Raider: Underworld doesn't interrupt.

Editor's Note: In the original version of this article, development of Tomb Raider: Underworld was credited to Core Design. The developer was in fact Crystal Dynamics.